Youth Soccer Tiers Explained: US vs Europe

If you’ve spent more than five minutes around youth soccer, the topic of of youth soccer tiers have come up. Then you’ve probably heard phrases like:

“MLS NEXT is the top.”

“No, ECNL is better.”

“Elite Academy is catching up.”

And somewhere in all of this, using only the inner voice there is the most important question:

What level is this actually?

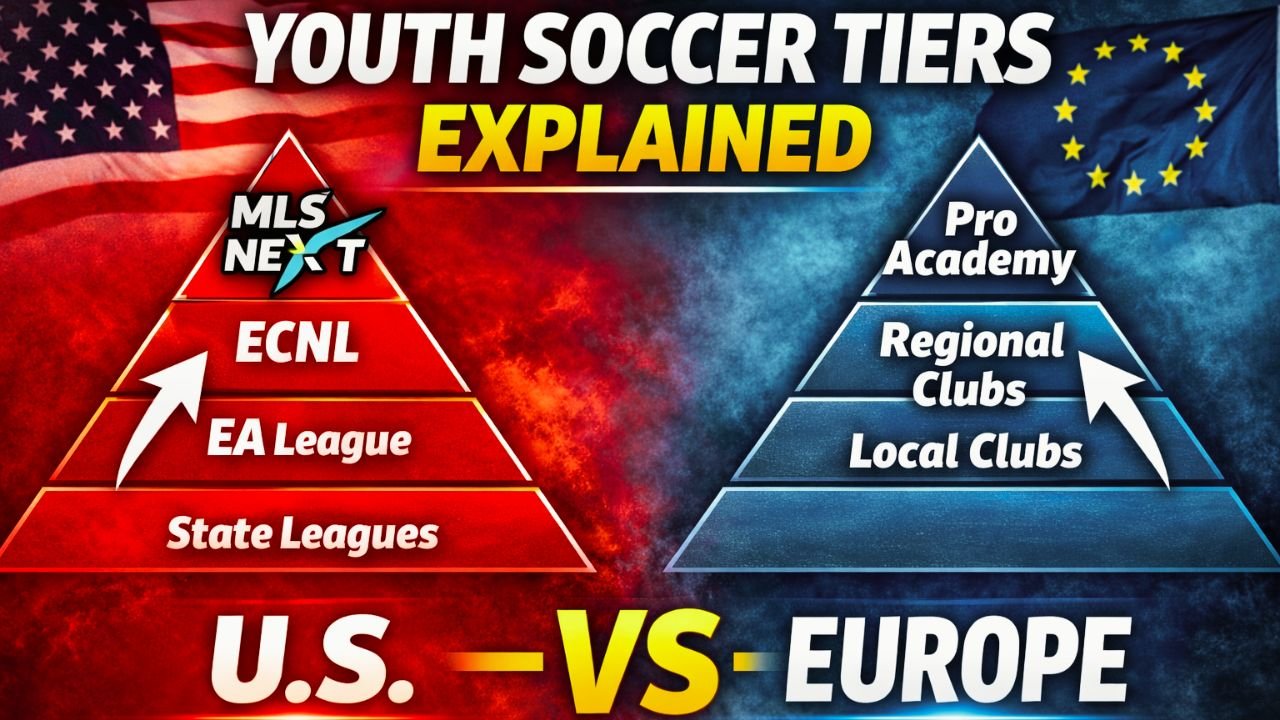

Let’s clean this up. Clearly laying out the youth soccer tiers in the United States… and then comparing them to how youth soccer works in Europe.

By the end of this video, you’ll understand why these systems feel so different, why arguments never end, and why “top level” doesn’t always mean what people think it means.

HOW THE US SYSTEM OF YOUTH SOCCER TIERS WORKS

The most important thing to understand is this:

US youth soccer is not a pyramid.

It’s a ladder built by organizations.

There is no promotion and relegation. Teams don’t rise or fall based on results. Instead, clubs apply, are accepted, or are excluded.

So, when we say that there is a pay-to-play by the players, there is a pay-to-play by the clubs, too. If a club has a great president that managed to file the paperwork and convince the league to let them register, then just send the money to the organization and they are good to go. Now here are the youth soccer tiers of the ladder.

TIER 1 – NATIONAL ELITE

At the top of the US system, we find the leagues that are supposed to contain the best players.

MLS NEXT

This is the top tier for elite boys. It’s officially run by Major League Soccer and designed to feed directly into professional teams and the youth national team selections are usually from these teams. Training volume is very high within the teams, and players often have individual practices, too. Competition is intense. And the best players are genuinely challenged every day. For boys, this is the clearest professional pathway in the US.

Girls Academy

The equivalent on the girl’s side is Girls Academy. It was founded in 2020, so it’s definitely suffering from inconsistency and structure in some areas. There are conferences and regions where it’s absolutely the best, while other clubs and regions are way behind. At the top, we are talking about the players that end up in the US Women’s National Team, so best in the world.

ECNL (Elite Club National League)

Then there’s ECNL (Elite Club National League), which often is just behind the MLS Next and the Girls Academy, but sometimes ahead. There are cities where the top team plays ECNL, and it recruits the best players in that city. That’s totally fine and not a downgrade. In both the girls’ and the boys’ side, the end goal is college recruiting. Most players will not end up playing professional, at least right away. Instead, they will aim to get a scholarship to play soccer for a college team. So, the structure is similar with several trainings per week, often 3 or 4, and often travel in different states for games.

TIER 2 – HIGH-LEVEL NATIONAL AND REGIONAL

One step below the top is where things start to blur.

Here we find leagues like:

- ECNL Regional League

- Elite Academy League (EA)

- National Academy League (NAL)

These leagues position themselves as elite alternatives or pathways upward. The ECNL Regional Leagues are firstly cheaper than the ECNL national league. Less travel and tournaments across the country. But often times that doesn’t correlate with the quality and there are incredibly good players playing at the top levels of the ECNL national leagues.

EA is even more confusing – the range between the top and the bottom EA team is even larger. The Elite Academy can be elite and compete with Tier 1 teams. Then there are clubs that joined the EA two decades ago and the entire coaching staff that created the club was replaced with coaches that see this as a job or a side job in some cases. The clubs focus on recruiting, marketing and finance, so that keeps EA happy and the other clubs enjoy battering them regularly to show dominance for their own recruiting.

Overall, all three leagues are competitive and have teams that practice usually several times per week, then travel to other states for games.

TIER 3 – STATE AND MULTI-STATE COMPETITIVE

This is where the majority of youth players live. Many of the clubs in Tier 1 and Tier 2 leagues have their second teams here.

Leagues like:

- US Youth Soccer National League Conferences

- State Premier Leagues

- NPL divisions

Here, the experience depends heavily on geography. In strong soccer states, this level can be excellent. In weaker regions, the gap to the top can be large. The practices are usually 2-3 times per week, plus a game on the weekend. The travels are regional, mostly within the state or the neighboring states.

For many players, this is a very appropriate level. Development still happens here and the goal for many of these players is to get to the upper tier by end of high school. Others will see that their bodies cannot handle soccer at competitive level on a 3-4 times per week schedule. And that is fine. They will probably not continue with the objective of becoming professional soccer players.

TIER 4 – LOCAL COMPETITIVE

Below that, we have local competitive leagues. These are organized. They have structure. They matter to communities.

But the emphasis shifts:

- Less travel – usually only 1 or 2 hours by car

- Less training – once or twice per week

- Less pressure – there really isn’t much difference if it’s top of the league or bottom

- Mixed coaching – some coaches have very little soccer knowledge, while others actually coach upper teams and this is just another team they coach.

This is still soccer. Just not a professional pathway. If a player doesn’t show the ambition to progress toward the upper tiers in their high school years, the chances become very slim to continue to a more serious soccer career.

The clubs in Tiers 1, 2 and 3, often have several teams in these competitions. They use them both as recruiting vehicles, where the best players of these teams try to make the upper team. Or simply they have them as business – they charge the players yearly fee and after paying the coaches and the fields, they have money left over to invest in the club.

TIER 5 – RECREATIONAL

At the base is recreational soccer. This is where most players begin. And for many, where soccer stays. The goal here is participation, enjoyment, and learning the game. Not exposure. Not rankings. Not scholarships. Sometimes there are practices, but even they look like just games. And the coaches are often volunteers, usually a parent of one of the players, focusing more on making sure things are safe and pleasant, rather than competitive. I’ve had players who simply don’t like the competitiveness of soccer. Others are having a tough time at school or at home, so they need a year or two where results don’t matter. Either way, it’s vital to have these leagues to spread the sport and also to give healthy environments for the youth.

HOW EUROPE YOUTH SOCCER TIERS WORK

Now let’s cross the Atlantic. Because Europe doesn’t argue about youth soccer tiers nearly as much.

Why?

Because the system does the sorting for them.

THE EUROPEAN PYRAMID

In Europe, youth soccer is tied directly to clubs.

At the top are professional academies.

These are connected to first teams playing in professional leagues. Players don’t sign up. They are selected. There aren’t multiple youth teams for each year, and it’s not about how much the families can pay. Instead there are scholarships and the demands are different.

Players often live together at a boarding school attached to the training ground. They have opportunities to practice with the B team or even the first team. They practice and play in the same philosophy as the seniors. Then you see these players having classes in the morning and play with the first team in the evening. The expectation of these players, even when they are in their early teens is to become professionals. So they think and live football every day, same as the first team.

This is Tier 1.

BELOW THE TOP

Under the biggest academies are:

- Smaller professional clubs

- Semi-professional academies

- Strong regional development centers

Players move up and down constantly, usually at the end of each season. In this case, it is very clear which team is at which level. A player released by Barcelona would go play for Espanyol, but not the other way around. A player released from Arsenal or Chelsea can stay in London and play for Millwall or Queens Park Rangers, but not the other way around.

Get released? You drop a level. Perform well? You get noticed. No applications. No politics. Just performance.

AMATEUR ELITE AND LOCAL CLUBS

Below that sits a large base of amateur clubs. The funding of these clubs cannot compare to the clubs at the top of the pyramid. The top clubs have more staff in their offices than the bottom clubs have players.

These clubs:

- Play in leagues with promotion and relegation

- Face stronger or weaker opponents based on results

- Exist within a real competitive pyramid

And here’s the key difference.

In Europe, the level finds you based on the performance on the field.

In the US, you choose the level based on the finances.

WHY THE YOUTH SOCCER TIERS FEEL SO DIFFERENT

This is where arguments start.

In the US:

- League names carry status

- Access often depends on money and location

- Players can stay in top leagues without winning

In Europe:

- Results matter

- Clubs rise and fall

- Players are filtered constantly

That’s why European coaches talk less about leagues and more about players.

And why American conversations often start with logos and acronyms.

THE MOST IMPORTANT TRUTH

Here’s the part that matters most.

The best level for a player is not the highest of the youth soccer tiers available.

It’s the level where they:

- Play regularly

- Are challenged but not overwhelmed

- Develop confidence and understanding

A bench player in Tier 1 is not automatically developing better than a starter in Tier 2 or Tier 3.

Development is not a badge. It’s a process.

THE IMPORTANCE IS NOT THE YOUTH SOCCER TIERS

Youth soccer doesn’t need more arguments. It needs more clarity.

If you understand the youth soccer tiers, if you understand the systems, you can make better decisions for players, parents, and coaches.

And once you stop chasing labels, you can finally focus on what actually matters. That’s the player.